The Horn of Africa is facing two diplomatic crises, Somalia recalled its Ambassador from Ethiopia and Sudan recalled its Ambassador from Kenya, Both countries complain of alleged interference in their internal affairs and threats to their sovereignty, Experts warn that the two diplomatic crises could threaten the stability of East Africa…

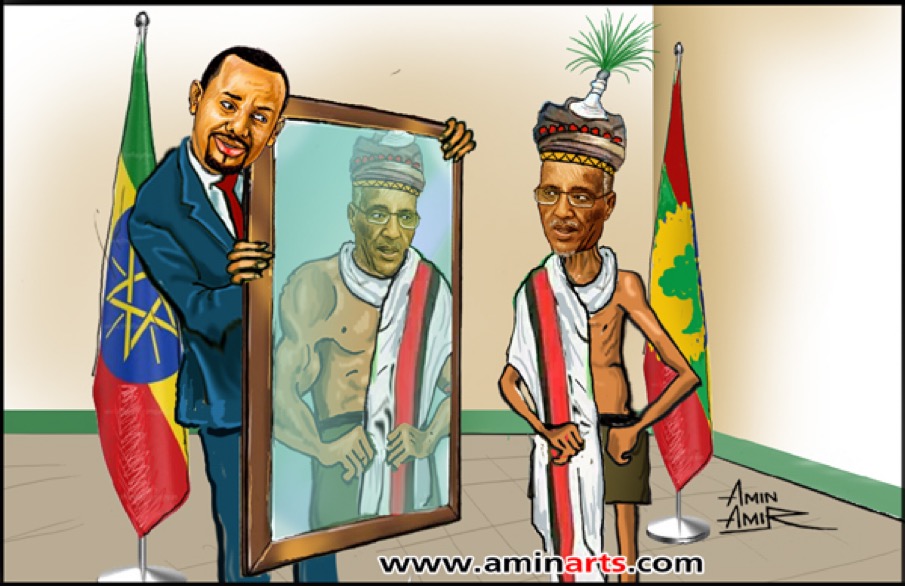

Somali leaders were angered by the agreement this week between Ethiopia and the breakaway region of Somaliland, The deal would give landlocked Ethiopia access to the sea and allows it to establish a military base in Somaliland, which Somalia considers part of its territory, To protest the deal, Mogadishu recalled its Ambassador from Addis Ababa.

Expert’s explained what the latest diplomatic spats mean for a region that has a history of border disputes and conflicts, So many foreign actors are at play in the region, and it’s creating alliances that are now also degenerating into inter-state conflicts because the Horn of Africa was basically suffering from internal conflict, but now, we see a spike of inter-state conflicts whether they are armed, but then they are conflict between states.

Legal consequences

From a legal standpoint, an MoU is not considered a binding agreement like a treaty and serves as a non-committal declaration of intent without imposing legal responsibilities on the involved parties. Either party has the option to end the agreement at their discretion, often without cause and with short notice. MoUs are not subject to the legislative procedures of oversight, review, and ratification as outlined in the Constitution. When utilized as a binding agreement, an MoU can become undemocratic and circumvent the constitutional safeguards put in place to preserve parliamentary sovereignty. At the international level, an MoU is not governed by treaty law and breaches do not result in international responsibility, nor is it obligatory to be registered under Article 102 of the United Nations Charter.

Hence, neither Ethiopia nor Somaliland have the legal standing to make an international claim regarding the MoU before an international court, and breaches do not automatically lead to compensation or reparations. Although it holds great political, diplomatic, and geopolitical significance, the MoU can be considered a mere “gentleman’s agreement”, with its true value lying in the realm of politics rather than law.

Political implications and geopolitical repercussions

For Ethiopia, the MoU diverts attention from internal conflicts, famine, and economic woes. For Somaliland, it potentially opens doors to international recognition, legitimizing President Muse Bihi Abdi’s government, but it may also intensify conflicts in areas such as Laascaanood and Sool. For Somalia, it is a violation of its sovereignty and territorial integrity, necessitating an outright rejection of the MoU and the seeking of support from regional allies such as Egypt, Eritrea, and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA).

What is more, the MoU and its diversion of attention could alleviate the rising tensions and possibility of war between Ethiopia and Eritrea, but the potential causes for these are still on the horizon. Geopolitically, if and when the MoU is implemented, Ethiopia will have naval forces in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden that are aligned with the UAE’s strategic interests. The UAE, with the support of Somaliland and Ethiopia, could thus reinforce its presence there. This could be perceived as a threat by the Jeddah Red Sea Council – the KSA, Egypt, Eritrea, Somalia and the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF). In addition, it challenges Djibouti’s role, especially its monopoly over port services to Ethiopia- the second largest population in Africa.

Conclusion

As diplomatic maneuvers unfold, the MoU between Ethiopia and Somaliland symbolizes the rising geopolitical significance of Africa and the effects of competition among great and middle powers. This MoU will be used by two alliances: the Saudi-led bloc, increasingly collaborating with Somalia, Turkey, and Qatar, and the UAE-led bloc, comprising Ethiopia, Somaliland, and the RSF. These developments showcase the intricate interplay of domestic politics, geopolitical interests of extra-continental powers, and the agency of pan African institutions.

National interests and various forms of power (economic, military, technological, demographic, and diplomatic) are projected, forcing new alliances and intensifying global competition. This scenario indicates escalating pressure on African institutions from both great and middle powers to align with specific blocs.